Cell phones drive them to distraction, brain imaging shows

Researchers have previously explored this territory, but Carnegie Mellon University scientists tried a new tack: They looked at the brain.

They used brain imaging to show that listening to a cell phone significantly reduces the brain activity that occurs during undistracted driving. This drop in brain function increases driving mistakes - such as weaving out of the lane or hitting a berm on the shoulder of the road.

Five states have enacted laws banning handheld cell phones while driving, but no state completely outlaws all types of cell-phone use.

New Jersey toughened its ban effective March 1. It is now a primary offense, meaning drivers can be fined $100 for talking on a handheld cell phone even if they have committed no other violation.

Scores of studies have shown that performing a mental task such as carrying on a conversation impairs driving performance, but the new research is the first to look at what is going on in the brain.

"So how big a deal is this?" said lead author Marcel Just, a neuroscientist and director of Carnegie Mellon's Center for Cognitive Brain Imaging. "If you're on a cell phone, it's just an added risk. I certainly don't want to be crossing the road while you're driving and talking on a cell phone."

A cell-phone industry official said he could not comment on the study itself, having not seen it, but said it made sense to reduce distractions while driving - whether it's dialing a number or putting on makeup.

"I think we all agree that there are numerous driving distractions that exist every day, and that wireless devices can be one of them," said John Walls, a spokesman for CTIA-The Wireless Association.

In the study, to be published in the journal Brain Research, 29 drivers, ages 18 to 25, used a driving simulator while inside a sophisticated brain-scanning machine called functional MRI. They steered a car along an empty, winding two-lane highway at a fixed speed of 43 m.p.h.

Then, they repeated the simulation while listening to statements of general knowledge. After each statement, they had five seconds to say whether it was true or false.

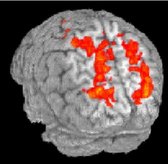

The MRI measured second-by-second changes in activity in 20,000 brain locations. It showed that listening caused a 37 percent decrease in activity in the parietal lobe, which controls skills involved in driving. Activity also decreased in the occipital lobe, the center of visual information processing.

At the same time, listening increased activity in the area of the cortex that is linked to language.

"You know the old TV commercial of an egg frying that said, 'This is your brain on drugs,'?" Just said. "Well, this is your brain on cell phone."

Although 29 research subjects may sound like a small number, it's actually a lot for a brain-imaging study, Just said, especially since the reduction in driving-related brain activity was seen almost uniformly across the group.

So were driving mistakes.

On average, the number of errors - such as wandering onto the shoulder or hitting a berm - jumped from 9 to 13 per driver. Weaving out of the lane also increased.

It could be argued that the simulation didn't accurately mimic real driving because the subjects had no pedals, and used a computer mouse to control the steering of their virtual car. The study's implications, Just and his coauthors wrote, obviously go far beyond cell phones.

"If listening to sentences degrades driving performance, then probably a number of other common driver activities also cause degradation, including . . . tuning or listening to a radio, eating and drinking, monitoring children or pets, or even conversing with a passenger."

Read the full study,

and driving laws

in each state at http://go.philly.com/health

Contact staff writer Marie McCullough at 215-854-2720 or mmccullough@phillynews.com.

Inquirer staff writer Tom Avril contributed to this article.